Alexandra Noel at Derosia

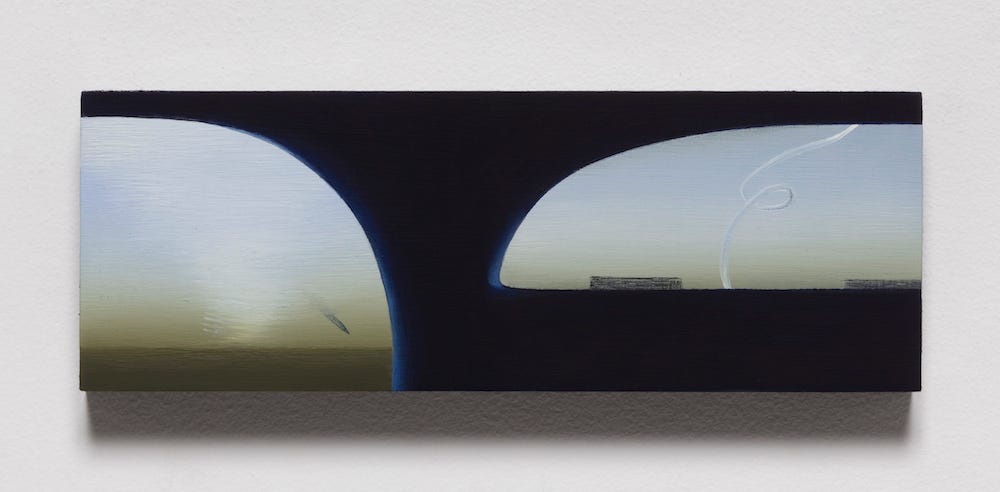

Alexandra Noel’s postcard-sized painted panel, Tornado in the Round I (2022), depicts a classic high-prairie twister scene, as glimpsed from the side and rear-facing windows of an automobile. It also stages—or rather, endlessly repeats—painting’s now enshrined dialectic between (illusionistic) figuration and (formal) abstraction. Two cropped vaults arched around these apertures would seem to situate viewers inside a rather old vehicle, or a distant past, while a stern horizon line to the left and an ombré olive-to-blue sky provides an almost otherworldly backdrop for the painting’s titular drama: a hazy funnel cloud of white—ever so slight—impasto. Two mysterious vectors punctuate the already imperiled scenery: in the lefthand vault, a thin black trail of what resembles smoke descends from the firmament at the right of the windstorm looking inexplicably more like (the battle of) Midway (1976) than The Wizard of Oz (1939); in the righthand opening, a tighter ribbon of white smoke does an ascendant loop-de-loop like an out-of-control rocket and a bright-white source of ignition is almost visible at the crest of the rearview pane. If there is a narrative to be gleaned in this work, then, like the twister bearing down, it’s far off in the distance. At first, it seems that we are catching “the figurative” as it trails off behind us. Yet, it’s hard to ignore the quiet, distant fury racing towards us.

Sublime (Up or Down) (2022), sits at the formal far-end of the illusionism vs. formalism dynamic, its a bar of light—a thick light lavender stripe—set against a dark blue background and running steadily up and then down from its corners to the central register of the small, square-shaped panel. The heavy band lightens, intensifies, and warms as it rises to the center. By the mid-twentieth century, rectangles and lines had become the hallmarks of abstract painting, as this mode of working the canvas wrestled the very definition of what constitutes a painting—the conditions imposed by the media—to the end of its developmental thread. Think an early Stella painting, or the art object itself, recognizing, feeling, its own presence, thus reaching its own maximally cerebral end. Noel’s geometry is present in Sublime (Up or Down), where it is granted more than just formal grace by virtue of an ever-so-slight glow that evokes a luminescent figure, an ambiguous opening in darkness, rather than geometric forms responding to a neutral “field.” Emphasis and intent are the objects on display here: the panel or picture “plane” is surely the implied, received structure but in what sense? Window or wall, picture or plane?

Noel sides with the window. A Newman “zip” or a Reinhardt rectangle might surely radiate or “glow,” but only by virtue of their simple, stark presence—figure on ground, or vice versa. It wasn’t until later, after painting “pointed” as far inward as possible and then made a detour into “pop,” that painters (including Stella) sought to incorporate illusionistic effects drawn from commercial art techniques and imagery, and claw them back into abstraction (with less than momentous results—from Jack Lembeck and Michael Gallagher all the way to Laura Owens). Noel calmly, though lucidly and effortlessly, picks a side, tenderly embracing illusion—the characteristic form—leaving the whole form-and-illusion discussion behind her, not necessarily in the dustbin of history, but far-off…in the dust.

Alexandra Noel

Three, Four

September 8 - October 29, 2022

197 Grand Street, 2W

New York, NY 10013

derosia.nyc