Elective Affinities at Chapter NY

The title of this beguilingly elegant grouping of sixteen works made by ten artists over the past two years—paintings and relief sculptures sharing a temporal affinity—has a long lineage worth unpacking. The term elective affinities takes root in the eighteenth century, when it served a proto-scientific function in describing the observed action chemical compounds have upon each other—a precursor to the formal laws that govern modern chemistry. Later repurposed by one of the great early scientific thinkers, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, it gave its name to a novel about love and lives lived outside the marital “bond.” Its initial scientific denotation would come to color a rich compound metaphor centered around what ow colloquially call “chemistry” … between two people.

Attractafty—might be the underlying principle behind all curation—it’s implied, more or less overtly. Ots, whether of an artistic nature or not, obtain meaning in relation, through the collective recognition of the threads that “connect” them. (This is true in the negative as well, when clear repulsion serves as a curatorial conceit.) If the curator is determined, inclined towards continuity, viewers will find affinities between the set of works displayed and the curator’s intended meaning. And yet, when the works on view are so recent—the product of a young crop of artists—and all treat each other, and their viewers, with such surplus grace as to render their sympathies elliptical, what story could the curators here possibly be able to tell?

In Goethe’s story, the aristocratic couple, Eduard and Charlotte, invite two visitors into their home and lives: Eduard’s old friend, “the Captain,” and Charlotte’s young niece, Ottilie. Alternative affinities form between the four and—characteristic of Goethe’s chosen form—conflicts ensue; established “bonds” between couples break and each character swaps pairs in diagrammatic fashion. Naturally—also as a matter of form, if not this novel’s titular paradox—the freewill vs. determinism debate arises, and is, accordingly, left unresolved. That the Belgian surrealist René Magritte painted a picture of a caged egg titled Elective Affinities (1933), based on a vision or revelation that came to him in a hallucination, doesn’t really clarify the hazy situation regarding the term’s deployment as a guiding curatorial principle either. And yet, as Peter Bürger reminds us in his Theory of the Avant-Garde, surrealism’s experiments with objective “chance”—born from Andre Bréton and Louis Aragon’s respective novels, Nadja and The Paris Peasant—as a productive yet ultimately roundabout detour on modernism’s endgame trajectory, which was, from start to finish, a preoccupation with form.

Bürger dismisses surrealism’s fixation on chance as a social/artistic affront, a breaking down or bypassing of society’s otherwise restrictive “means-ends rationality,” dependent, in particular, upon producing meaning. For Bürger, the surrealists’ claim to conduct social and artistic protest by seeking out “the marvelous in the everyday,” amounted only to an abstract protest against “sociality as such.” Surrealist endeavors, he remarked, would serve instead to foreground the role that “congruent semantic elements” play as a common denominator in constructing meaning. We inherit from the surrealists (ditto, Dada) their early embrace of ambivalence—as protest or otherwise—and, in spite of their flirtations with “fate,” the suspension of resolution, the paradox of free will vs. determinism as one that plays out formally, in the novel or anywhere else it is… advantageous. Given this, might the most recent Elective Affinities simply be using the rich complexity of this compound term as an evocative, catchall cover?

The works on display in Elective Affinities each possess a natural accord of cool and calming shades of gray and unsaturated colors, creating a near-homogenous tonal palette or feel in the exhibition space. Like Goethe’s grand metaphor, this is as much a fact of physical observation as it is a matter of sentiment. At the same time, moments of intensity—both in color and character—punctuate the overarching serenity. Amy Stober’s wall-mounted polyurethane casts of handbags are certainly stand-outs, as they form aberrant yet ultimately quite allusive reliefs. A Few of My Favorite Things (2022) shows what looks like an open clutch that has been given a monochromatic treatment reminiscent of Charles Ray’s Unpainted Sculpture (1997) of a car wreck. This bag is mounted bottom out, on its side. What solicits maximum attention: the intricacy of the details Stober has hand-decorated in acrylic on the object, gracing the purse’s derrière with a charming little painted tableau that’s equal parts trompe-l’œil date book organizer and teenage boudoir.

The bright Flashe tones found in Gerald Euhon Sheffield II’s strange, searing hot sunset in panorama (paggank) (2022), with its equally odd, hotdog-like cattails poking in from the left-hand margin, offers comic relief. This everywhere-and-nowhere mental landscape, done in tondo, may seem coy, especially with the back of a fawn’s head at the bottom peering along with the viewer. But elements like the all-too-short, perspectively-disjunct evergreen near the middle ground heighten a sense of erotic playfulness that can only be found elsewhere in Paul McCarthy’s similarly squat—though monumental in scale—green “Christmas tree.”

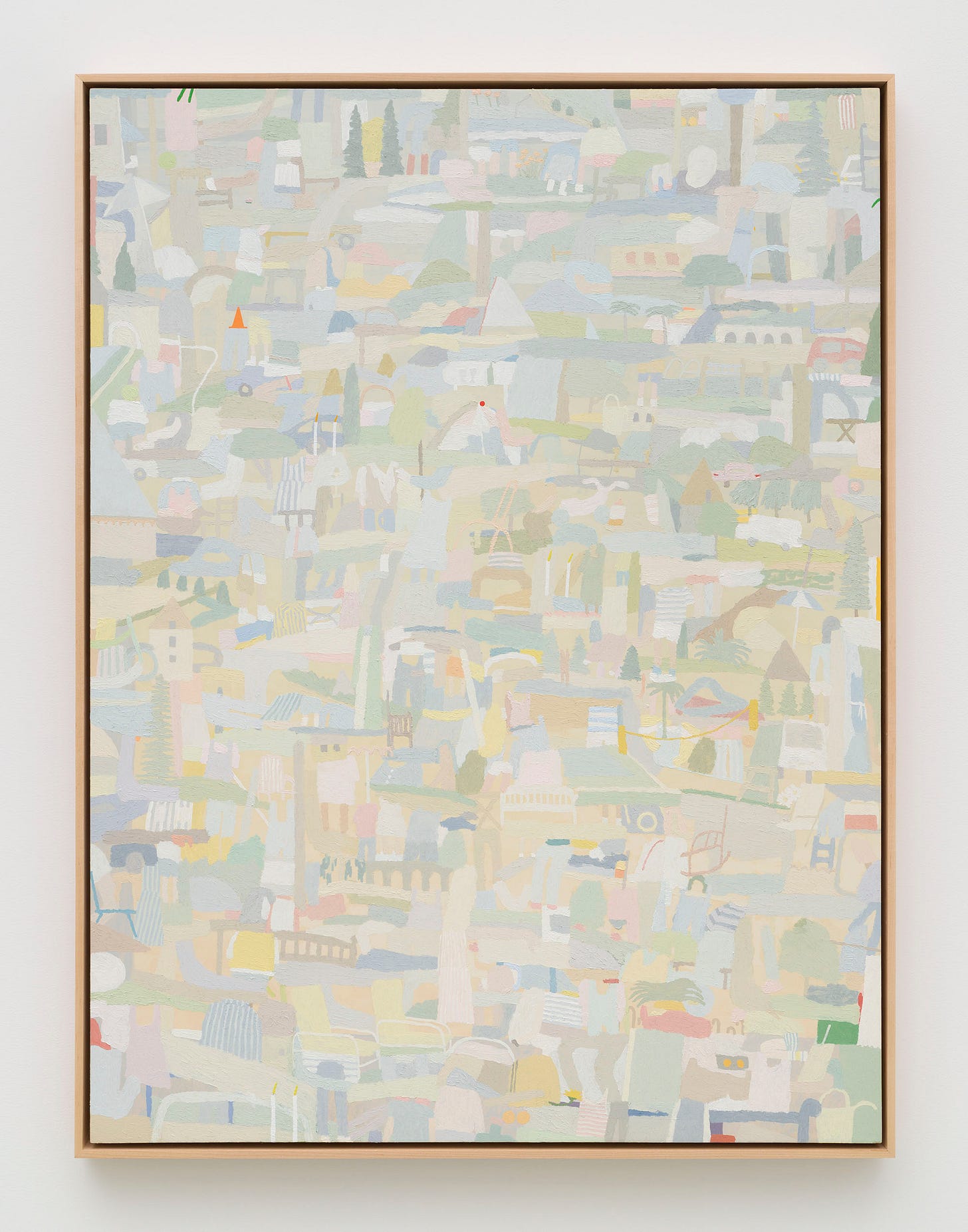

Mariel Capanna’s delightfully well ordered, horror vacui “landscape” painting, Red Light, Bucket, Candles, Sails (2022), dabbles almost exclusively in pastel tones, pumped up by mixing in marble dust with her materials. The silhouetted shape of a bright orange traffic cone and a red dot (a minute stop signal?), punch themselves into the otherwise serene setting, which starts to look like a child’s traffic/town play mat with its compressed, quasi-aerial perspective. Green Light, Bucket, Candles, Sails (2022) a painting on paper, offers little more than the cone and a green dot, set against a very mild, ombré background.

Otherwise, what seems serene starts to look staid. These works behave well together because apart they represent a procession of styles mum in their own defense. Accordingly, we get: faux naïve, or perhaps just naïve, paintings by Coco Young; seemingly unsparing neo-neo-expressionism that is really just unnecessary from Hwi Hahm; the urban/primitive pastiche, virtually trademarked by the perennially cool Basquiat, brought into cellulose relief by Nickola Pottinger; abused tapestry in the spirit of Scannable from Justin Chance, etc. It’s the ’80s again, the decade in which the oldest crop of these artists were born, with its edges rounded off. We’re even “back” down on Walker Street for chrissake.

Using love-outside-marriage as the nucleus of his plot, Goethe’s novel evokes moral questions—again, the inexpugnable issue of “freewill”—and in its day, provoked objections and outrage from many readers. Its characters cast aside what was, at the time, a matter of assiduous and vigilant duty—upholding marriage as a social institution. Yet, condemnation is by no means the moral vector Goethe pursues in his Elective Affinities, his is a softer judgment.

In one of the book’s early, central scenes, a stone-laying ceremony is held on Charlotte’s birthday, with many rural German villagers in attendance to commemorate the beginning of construction of her new garden villa. More than just a semisecret nod to Goethe’s brothers back at the lodge, this moment includes a lengthy monologue by the well-dressed stonemason officiating the ceremony, and the placing of what we might call “time capsules” in the building’s foundation stone. It cements the notion of temporality—one’s life-span—as being the substrate upon which all moral action rests, both in terms of the here and now and of our enlightened foresight. The scene concludes with a drinking glass, engraved with the initials “E” and “O,” ceremonially tossed into the air and caught by a villager overhead on a scaffold, which Eduard (mis)takes—an offense Breton might also be accused of making in his novel—as a sign of Fate’s approval of his perhaps reckless love for Ottilie. As David Constantine puts it in the introduction to his translation, Elective Affinities is:

[M]oral in the way that all great literature is moral: it quickens, through its art, an awareness of issue which we may call moral if by that we mean having to do with better or worse ways of living.

Thomas Bernhard, Austria’s twentieth-century master of a fiction of brooding social observation, abruptly drops this stone-laying scene from Goethe in the mouth of his mentally decaying aristocrat, Prince Saurau, whose crazed, rambling monologue forms the bulky second half of Gargoyles, a sustained meditation on rural Austria in a period of postwar transition. The Prince’s extended diatribe is an intriguing experiment in form, an easy inhabitation of mental illness that presents insanity with palatable coherence. The Prince’s reference to Goethe’s Elective Affinities comes and goes in a single paragraph, and it is unclear what, if anything, it means. Is it a sign of the Prince’s mental faculties momentarily restored, or a clear indication of their departure?

Bernhard’s gifts were best expressed in his unbroken-paragraph-cum-novel Woodcutters, the ultimate semi-autobiographical gripe about his surrounding world of bourgeois Austrians with languishing artistic pretensions. If their goal was to realize an artist’s life, they merely achieved an existence that, at times, passed as “artistic.” We are offered, for instance, the narrator’s one-time “friend,” Auersberger, who long ago squandered the moment during which he could have seized something like a life well-lived. As Bernhard’s narrator acidly observes, Auersberger—the naturally talented would-be composer—sought out the wrong goal: “It was…his life’s ambition to be an aristocrat, nothing less: the sad truth is that he would rather have been a witless aristocrat than a respectable composer.

These artworks’ shortcomings are not necessarily a matter of anachronism—bearing too strong a resemblance to styles from the past—although they are guilty of this all the same. To be fair, the artists are all very young. Bernhard’s middle-aged narrator is occasioned to meet—after thirty years or so—the quasi-artist friends from his formative, aspirant years. Being older and wiser, he realizes that he had surrounded himself with mere pretenders and dilettantes. Reflecting upon his past and inflecting it with the bitter distaste of his present, he understands that his former associates’ problems lie, ultimately, in their work: none of them had the ambition or foresight to actually produce anything really challenging. Auersberger, once a real talent, certainly never aspired to as much. It was never his goal.

Political economy was born from European societies’ self-reflections, as they made their earliest exits from their feudal pasts and held forth toward their subsequent enlightenment(s). What we inherit from this now, perhaps, is a dead (axed) branch or knowledge of a virtual maxim: that pervasive rent-seeking behaviors are something like the key apparition of a more generally moribund society. Accordingly, most of the rot we can smell today is traceable back to a vast and deep entrenchment of certain zero-sum conditions, ones that elicit such behaviors. Academia is in no way shielded from this decay; doubtless, the ivory tower has sunken into the shit. There too, one will find a patchwork of pathetic gargoyles clinging to minor, decaying little fiefdoms. Today, more than ever it seems, a surefire recipe for success in an MFA program is ultimately sure to send talent and ambition running in a self-consuming circle. For the artists in Elective Affinities, or any artists working at the moment, to be truly successful, they must endeavor to be free… free of the risk of disappointing present expectations.

Mariel Capanna, Hwi Hahm, Molly Rose Lieberman, Nickola Pottinger, Amy Stober, Coco Young, Olivia van Kuiken, Justin Chance, Elizabeth Tibbetts, Gerald Euhon Sheffield II

Elective Affinities

September 9 - October 8, 2022

60 Walker Street

New York, NY 10013

chapter-ny.com