Nancy Dwyer at Theta

Is there any risk in adopting a new technology too early, embracing a new software or gadget before it becomes ubiquitous, another part of daily life? Gizmos have a social existence to be sure, one that is almost always synonymous with “technology” as it has come to be understood. We like to imagine the ur-version of a hammer or wheel being used by a single individual, but it is through their widespread use that these things become extraordinary and socially transformative. Language, on the other hand, is more clearly a social phenomenon, one perhaps without this hypothetical first instance. We no longer care to imagine the lone, first user of a language, much less its originary utterance, without first conceiving of its development in human interaction. The history of technology is littered with unacknowledged “utterances”: false starts, almosts, and now-funny-looking failures; likewise, there are just as many dead and unrecognizably distorted languages as there are obsolete and disappeared technologies. Obsolescence always appears awkward and, in a sense, unintelligible in the present-day context.

What does an artist risk, then, by departing from the forms and conventions of a movement or style to which she has come to be associated? Estrangement, alienation, public rejection? Assembled at Theta for the exhibition How About Never?, works by so-called “Pictures Generation” artist Nancy Dwyer from the last three decades that hardly present any pictures at all, may answer this second question. In addition to being a practicing artist for decades, Dwyer has previously worked as a commercial sign painter. Unsurprisingly, Dwyer’s paintings and painted-object sculptures play with language (the English language), using seemingly known phrases rather than the coded images interrogated by her fellow “Pictures” artists. Here, language-as-text (script) forms the actual—albeit warped—“image,” with uncanny optical arrangements that spill from the linguistic progression of familiar phrases.

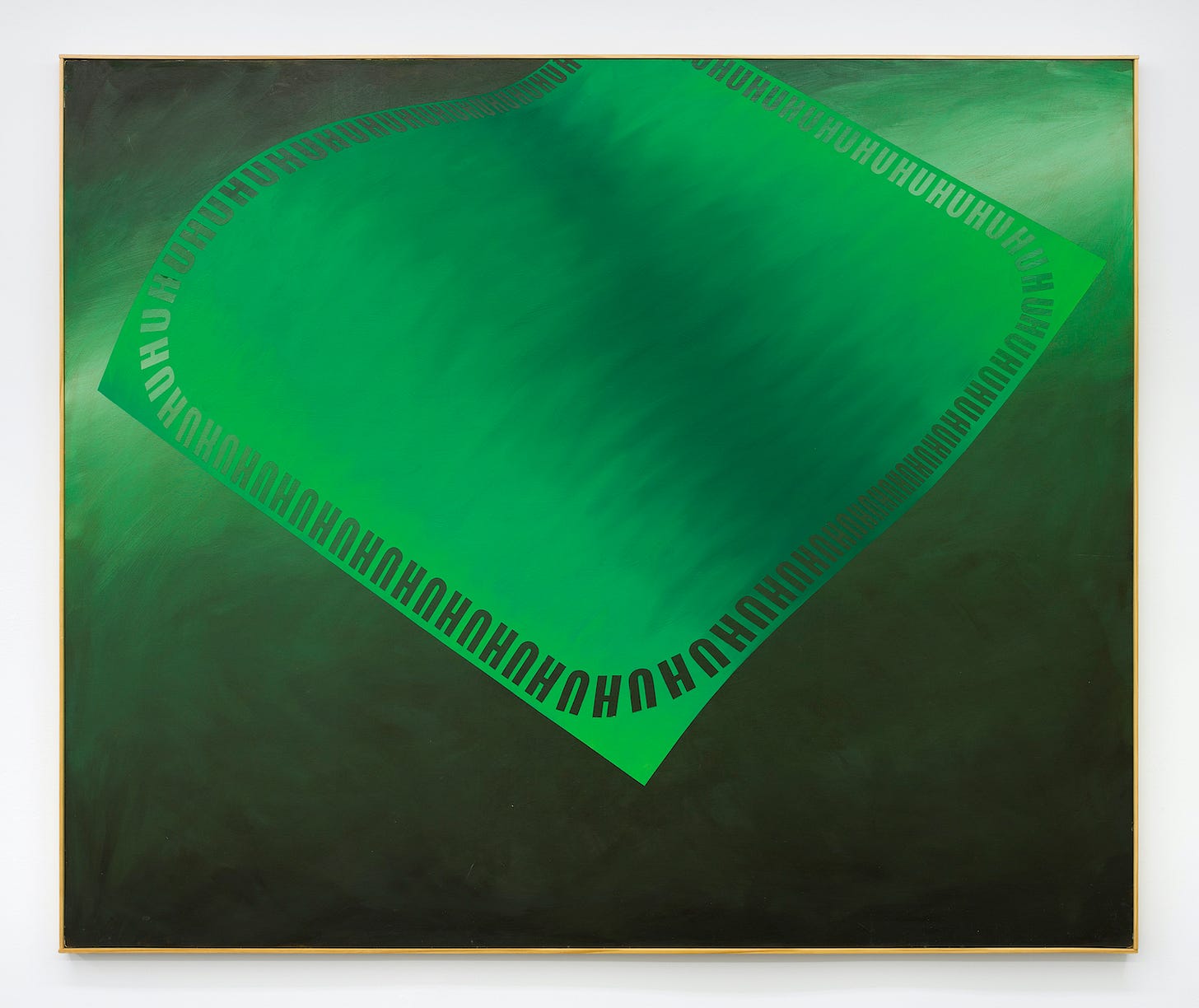

Consider Dwyer’s 1998 green-scale painting, Uhuh. The onomatopoeic phrase is repeated in a never-ending, ourobororatic loop around the outer edge of a flying-carpet form that is three dimensionally rendered and “floats” slightly-above-center, comprising the painting’s lone figural motif. It is the visual expression of a mind gone blank, an affirmative “uttered” until all expression is emptied out. On the other hand, this “sheet” form hovering at the fore of a nothing-and-nowhere background may, for some, evoke the counterpart to “Clippy,” the Microsoft Office paper clip—or, rather, the visual/interactive manifestation of that program’s user “help" interface, which took the form of a cartoonish, animated paper clip, with eyeballs and singularly expressive brows, that “ride” atop a furling sheet of yellow, lined notepad paper.

Clippy’s origin story begins in the late 1980s and early ’90s, in the research of social science Stanford University professors Clifford Nass and Byron Reeves, which essentially posited that humans would interact with computers as they do with other humans if these interactions could be suitably anthropomorphized. The objective here was to avoid user frustration at a moment in history when computers and their software were much more frustrating to operate. Back then, an errant key stroke or command was liable to throw the machine for a loop and into a freeze, driving the user out of their mind. Clippy quickly became a notorious object of ire due to its clumsy attempts to put a positive spin on machines that often merely spun their wheels or spun right out of control. With this bit of technology’s past in mind, Dwyer’s painting deploys such empty-headed, flabbergasted frustration in a collision between “old” and “new” media, reminding us that technology’s false starts can be fertile for making quietly fantastic art if the failed technologies and all their irritating irksome inadequacies are kept at arms-length—that is, if the medium remains a familiar one. Like painting.

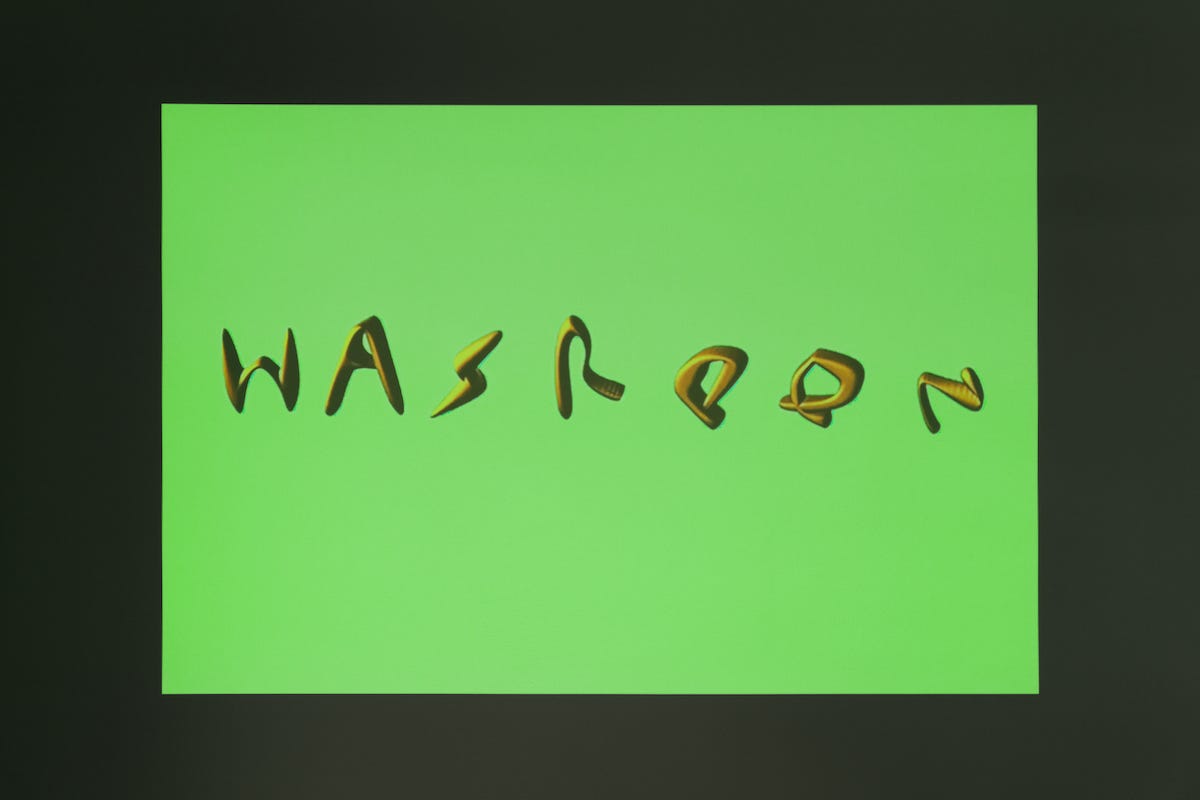

Here’s a proposal for understanding art made using “new media”: an artist’s direct engagement with new technology has a shelf life proportionate to that of the technology itself, except when this engagement is applied to, or directed at, the technology as an object already in a state of decay and/or flux. Dwyer’s digitally animated video Hasbeen Wannabe (2002) might as well prove this rule in its deployment of the once-captivating rendering of graphicized text into a dull digital artifact. And yet, the language she employs hints at the possibility that Dwyer may have anticipated this decay or change all along, chasing a then-future resonance between script and scenario. The video itself shows the 3D renderings of rounded letters spelling out “has been” and “wannabe.” Neither term stands alone, as it continually morphs from one phrase into the other.

All this talk of technology may be leading directly to Dwyer’s ultimate object: language as such. After all, Dwyer was a member of the Pictures Generation cohort, a loosely associated group of artists whose banner was perhaps superficially misleading, as their hallmark was to employ known imagery in the deconstructive service of exploring linguistic predetermination. This “group” coalesced in the late 1970s when the work of French philosopher Jacques Derrida was beginning to stir the anglophone world. Derrida’s signal Of Grammatology, for instance, focused on the interstices between spoken and written language and social structures, effects and hierarchies carried along and implied by the privileging of the spoken word. He considered its outsized role in the construction of Western reason, where Logos—the word of god, or the supposed first instance of a language necessarily determined—took deep root. The gambit for Pictures artists rested in the application of this then-new Derridian technology (“deconstruction”), in as far as artworks—or, more broadly, just “pictures”—could be “read” as “texts.”

Dwyer’s specific take on this broader practice has been to home in on irony and puns—namely, instances in which the spoken word is arrested, suspended or otherwise caught in its own graphic representation. She performs the unique fillip of always, and in her own way, ultimately preserving an ambiguous hierarchy between the two poles. Take her piece Big Ego II (2011) an 8-foot-long inflatable sign—or is it a logo?—that spells “EGO” in bulging yellow nylon. (Sign or logo, it’s far too large to display in Theta’s cozy, subterranean gallery space.) It takes a split-second to note the correspondence here: that the language represented in the form is doing the very thing that the term “ego” most often tends toward: puffing-up a subject’s sense of self.

Dwyer has created a much smaller piece of three-dimensional, “mobilized” language with Thinking Machine (2010). It is a small, rotating, unpainted wooden contraption set on a roughly waist-high shelf. It looks simple, like an old-timey toy—imagine an Amish GameBoy. A horizontal spindle bears the block-letters I and F on one side of its axis, and the letters T, H, E, and N on the opposing side. A small crank arm on the right side allows “users” to rotate the letters such that the two terms can produce a basic conditional sentence structure. The device automatically activates and locks us into this structure, this language hierarchy; whatever way you spin it, forwards or backwards, you are looped into the if/then construction. Yet again, visually, the piece exposes a little correspondence, the presence of the if/then construction at the heart—or center—of the letterforms themselves: the “IF” as a shape is actually embedded in the middle of the characters that spell “THEN”—specifically the H and E. This is a pun of sorts in that it turns on language (script) but cannot be easily formulated or expressed in language. Is it a game of hide-the-grapheme or find-the-phoneme? There is no stylistic convention for expressing such “subatomic” decompositions of the alphabet itself… with text (save for the ugly hash served up by semioticians). Forget the copy editors then, such crisscrossing and cutting apart of conventions—whether or not they are those of language, script or “pictures”—is the work of artists plumbing something like the conceptual, or post-conceptual, expanded field.