Kye Christensen-Knowles at Lomex

These days, regarding the art of the present, heterogeneity reins as the oddest and most uncomfortable of impositions . . . for artists. It is the requirement to work without requirements: Figuration vs. abstraction? Style? Content? Whatever, you decide. Inasmuch as “the (human) figure” is a form with a residual lineage that happens to be quite extensive; it is now also a “site” in which some artists, critics, and theorists have come to see a form-of-surplus, a surplus form of content. For Kye Christensen-Knowles and many others this supplemental value is male homosexuality itself; it was there all along in the classical subject, the apogee-form for male-homosexual discourse and all nearly all other forms of “figurative” discourse as well, and Christensen-Knowles amplifies, disturbs, and exceeds the classical, figurative tradition's supposedly innate harmonies with a stylistic addendum all his own, an idiosyncratic if not haunting supplement to his firmly-rooted faith in mimesis and by extension (allowing for a slippage “back” to a seemingly antiquated association of thought) humanity itself.

Lomex gallery in Lower Manhattan has recently mounted Herein, which includes a number of his paintings (all oil on linen) and two small sculptures (all works dated 2024). Divided between two spaces across the street from one another (Walker Street in Lower Manhattan), the work in the show is clearly split in terms of its nature and subject matter. One space (86, 3rd Floor) contains what might be called—anachronistically, perhaps—“society portraits,” done by a John Singer Sargent of a twenty-first century, downtown bohemia. Another (89, #2R) is filled with paintings which delve into an entirely distinct, atemporal, or, rather, narrative—that is, science-fictional—register: a little world, or worlds, of obvious simulation.

Insistent mimesis can read like a hold-over from the past—in general and herein . . . that is, in Christensen-Knowles’s show where the works come off, at least at first, as scholastic in light of an (aforementioned) interminable range of options. Yet, societies and civilizations are not built in a day, nor do their fundamental components—like language and culture and the multitude of constituent “practices” and “institutions” therein—arrive, fully-formed in the span of a single lifetime or generation. They are born and advance, within time and place (history), and eventually fade and die over durations which exceed that of the single individual. Hence, Michel Foucault’s preferred epistemological instrument to apply during his lifetime of study of as much—occupied as he was with such phenomena over the course of his career—was Nietzsche’s “genealogy” (of morals, etc.). Foucault’s keen interest in the history of sexuality has in particular, since, won him an apostle class of “queer theorists” who consider his work to be essential to the foundation of a, now very active, academic doctrine. Inasmuch as Foucault’s thought is indebted to Nietzsche—and it is, as much as it is to Marx (if not more so, and an overly concise explanation might consider him a fusion of the two)—the will to power weaves its way through much of Foucault’s writing; and yet, the reader of Marxist inclination might find power, as it appears in Foucault’s work, to be lacking a sufficient genealogy of its own.

What does this sketch have to do with figure painting? The obvious answer would be to scribble a little more about “the body,” Foucault’s preferred “site” from which to enter and begin to explore his various, over-arching subjects and themes (sexuality, justice, madness, etc.). The body is, after all, an enduring human fact—one indelibly linked to, but materially distinct from, the ideational practices of societies and cultures over the ages. In as much time, artists have taken up the human form with just as much heterogeneity.

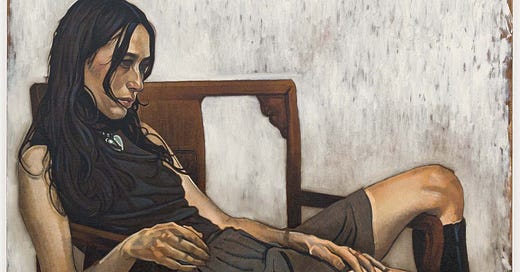

86 Walker Street—coming in from the stairway—one finds Leah, a delicately painted, nearly full-length portrait of a young woman. She is quite comfortably reclined on an almost overwhelming, yet accommodating, chair—like an up-to-date Lady of Agnew and just as stunning, but set in profile against a scrubby white background, with her pensive gaze sent sideways. She is an exercise in contrasts: her skin is rendered in soft and warm hues, while her hair, vacant eyes, clothing and over-the-calf boots anchor as much with their deep browns and blacks—delicate beauty with a well-balanced dark side. Zoe stands Sargentine, in full-length, in a pink ensemble that looks dear but not overdone, save for a brown fur or feathered accoutrement of some kind worn over her right shoulder. Its strands, along with those of her matching brown hair, are rendered with an aggressive and excessively organic specificity, almost like an array of thorns and talons. The room is filled with such paintings of the artist’s friends and intimates, including a chiaroscuro self-portrait with the artist wrapped in a fluffy, fur-collared coat and Henry, a painting of a young man in repose, his face and hand visible, while he is otherwise enveloped by turquoise waves of bed linen.

The gallery has been partitioned—slightly. A temporary wall has been set up at the front of the building, creating a separate, smaller space: a “back room” if you took the stairs up; otherwise, the building’s elevator opens directly into this street-facing antechamber. It is home to the “dirty” work: two male nudes. In this sense, the space has morphed into something like the video rental stores of yesteryear, with the conventional offerings occupying most of the real estate up front and pornographic selections hidden in the back. Rocco is a starkly lit full-length nude of a lean but muscular man’s backside, illuminated from above. He leans with his left arm up and perpendicular, resting on a four-drawer filing cabinet. His body is presented—or simply illustrated, or illustrated rather simply—with an economical range of values: a deadpan brown fills out most of his form, mostly as a silhouette of sorts, while a pinkish orange highlight color is used to show off the elaborate formation of musculature that makes up his upper back, shoulders, arm and, err . . . uncompromising upper buttocks. Next to him is an untitled painting of a man bent forward and buckled BDSM-style to the underside of an upside-down chair. A sliver of sidelong light, seemingly emanating from a cracked-open door, strikes his bare backside, which can be seen here as both available for easy sexual access and as a sort of substitute for his face which is bent low and hidden behind his left leg and arm.

The two small-scale, painted, yet more or less monochromatic sculptures of thin, nude, anonymous, and genital-less, “male,” or merely humanoid, figures stand on equally slender pedestals in the center of the room. They are more stylized—rendered with subtle ivory, gray, and turquoise hues—than their already-quite-stylized counterpart paintings. That is, the two sculptures accentuate Christensen-Knowles’s already obvious obsession with stylistic surfeit, a composite of inter-war personifications, or deformations, of the figure under historical duress. (It is also worth noting the supplementary, if not sumptuous, role that teal takes on in Christensen-Knowles’s amplified classicism: the product of a—as mentioned—scholastic approach to painting where warm-versus-cool color contrasts reign. However, teal blue appears often and out of key, that is, off-scale: a deliberate misuse of and stress on the technical and formal parameters and expectations that the artist has already so carefully laid out for himself.) Christensen-Knowles is clearly working in an historical register well beyond Sargent, figurative master and singular stylist that he was. Or is it an ahistorical “style”? Søren Kierkegaard had it that “irony” was something middle-ground in historical development, a sign that a subject, a rhetorician or otherwise, had become aware of what had been and was not yet the embodiment of what will be.1 Can the conscious production of history in art, in as much as conventional art history teaches us that history moves hand in hand with “style,” ever be anything but? In other words, is such simply pastiche? Why then the return to a “return to order” in the third decade of the twenty-first century? Has the American Weimar proceeded any differently than the first go around? Or is all this—"historical movement” in general, and whatever you want to call this present in particular—a teleological necessity, a chimera, itself a byproduct of interpretation?

History has seemingly completely disappeared in the science-fictional works in 89 Walker space, lest we remember that science fiction is always a narrative statement from the present about the present. These paintings are as monumental in scale as they are manipulative: of our sense of “humanity,” the human form, and history and the future. And yet, they are less shocking than their counterparts across the street. Perhaps this is because their overbearing stylization works its violence upon beings that we would never recognize as anything like ourselves or places we can barely see as anything but merely similar to our world. Strange and distant, the subjects in these paintings appear as muscular and sinewy anthropoids, or bizarre animal hybrids, or simply hovering orbs of some sort. At seventy-five by one-hundred-and-sixty inches, the conjoined diptych Angel of History is the most monumental painting in the room if not the whole show. It is a brownish-ochre battle scene which pits, from left and right, two converging masses of contoured or otherwise abbreviated figures against each other in some sort of otherworldly clash that is almost unintelligible in its scenic density. It reads like a frieze as its two dueling legions meld into something like Marcel Duchamp’s final figurative painting, his send-up pastiche of cubism, Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2, (1912). (Was a then deeply frustrated Duchamp in some sense parting with the past, and his past, gayly?) Christensen-Knowles doesn’t seem to be laughing much with this work, yet how serious can sci-fi really be?

Walter Benjamin used Klee’s Angelus Novus (1920), which he was the first to purchase, as an exemplum in his late and final, and deadly serious, “Theses on the Philosophy of History” (1940).2 Therein the angel is seen as “holding back” the pileup of destruction that is historical “progress” per se, something only the prostrate dead can possibly attest to. Brief as they are, the theses deliver Benjamin’s philosophy at its most enigmatic if not its densest and most explicitly theological. The only antidote to the continual destruction and “wreckage” that is history’s progression is the ultimate break, the revolutionary or “messianic” moment—or, rather, its anticipation in every lived moment. And what is the function of science fiction—as literature, film, or even painting—if not to anticipate the future, utopian or otherwise?

What do the two spaces, these two distinct bodies of work, say together? They stage the stakes and limits of “queer” expression as it stands today. Is gay desire, still, a revolutionary or socially transformative force, or is it caught, like many other “revolutionary” political projects, in a perpetual present wherein desire has come to look less like a liberating force than the lubricating medium that allows capital to penetrate and restructure “reality” to the point that it secures as much as some kind of "closed" or “resolved” totality? Foucault brought back Bentham's panopticon, reintroducing the "ideal" prison as a conceptual frame with which to view contemporary—that is, “liberal”—societies’ overriding operative social mechanics . . . in whole. Here, we can, and must, preserve and stress the dual meaning of the term: both “liberal” and “Liberal”; and as far as the panopticon is concerned, we should remember that “permission” is essentially bound to its effective operation. Christensen-Knowles’s insistence upon a heavily accented academicism in his painting and sculpture then might just be a coy assertion of an element of friction.

Kye Christensen-Knowles

Herein

November 9, 2024, - January 18, 2025

LOMEX

86 Walker Street, 3rd Floor & 89 Walker Street, #2R

New York, NY 10013

Søren Kierkegaard, “The Concept of Irony, with Continual Reference to Socrates,” in The Essential Kierkegaard, ed. Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong, trans. Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), 20-37.

Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (Boston: Mariner Books, 2019), 196–209.