Local Turbulence: Art of the Outmoded in New York, Part 2

ART CLUB'2000' at Artists Space curated by Jay Sanders, Jamie Stevens, and Stella Cilman, October 21, 2020 – January 30, 2021

Remember the ’90s… as they were? Having returned as a trend—led by youths with little, if any, memory of those years inching towards the new millennium—the decade is now being revisited, perhaps, as we’ve always wanted it to be. Artists Space has deftly let the youngsters of that decade answer the question themselves with Selected Works 1992-1999, the first comprehensive survey of ART CLUB2000 (AC2K), a group of seven Cooper Union undergrads who took the mysteries and anxieties of both the insular art world of the ’90s and its broader consumer culture—as well as their privileged place within both1—as their subject.

Like many great rock groups composed of acerbic youngsters, AC2K’s first effort was perhaps the purest distillation of their telos, if not the sharpest articulation of their overarching drive, drafting the blueprint for their subsequent efforts. In 1993, the group’s Malcolm McLaren-esque gallerist/manager Colin de Land booked AC2K in the summer slot in at his downtown New York gallery, American Fine Arts, Co.—an opportunity that De Land would continue to extend over the next seven summers. The group put together Commingle, a wry installation-based study of then-reigning retail brand, The Gap, which has been elaborately recreated at Artists Space.

Before any artworks were actually exhibited (back in 1993), the group launched a publicity stunt aimed at provoking the retail giant while promoting their own debut. AC2K produced a faux Gap advertisement, mocking the chain’s then-recent “Individuals of Style” ad campaign—one of the first of a now-ubiquitous advertising strategy consisting in enlisting a diverse group of celebrities to position the brand as representative of a pan-cultural cool. Offering their wares as symbols of a personal taste for culture both high and low to a retail subject who would likely fancy themselves as being in-the-know (if not one-step-ahead of the latest trends), The Gap extended a cynical handout to their consumers’ sense of subjectivity, nodding to the shoppers’ own feeling that demonstrably good taste must equal a demonstrable superiority of the self.

The original Gap ads featured sharp black-and-white photo portraits of pop and counter-cultural figures like Joan Didion, Madonna, Lenny Kravitz, William Burroughs, and Leo Castelli,2 the sort of figures whose professional achievements and/or personal aura the young members of AC2K might—in the minds of marketing experts—otherwise aspire to emulate. In the AC2K mock-up, De Land was featured as one such “individual of style” complete with The Gap logo in the lower right corner, a clear breach of copyright which quickly prompted The Gap’s legal representatives to fax over a cease-and-desist letter to American Fine Arts, Co. after the ads ran in a 1993 issue of Artforum.

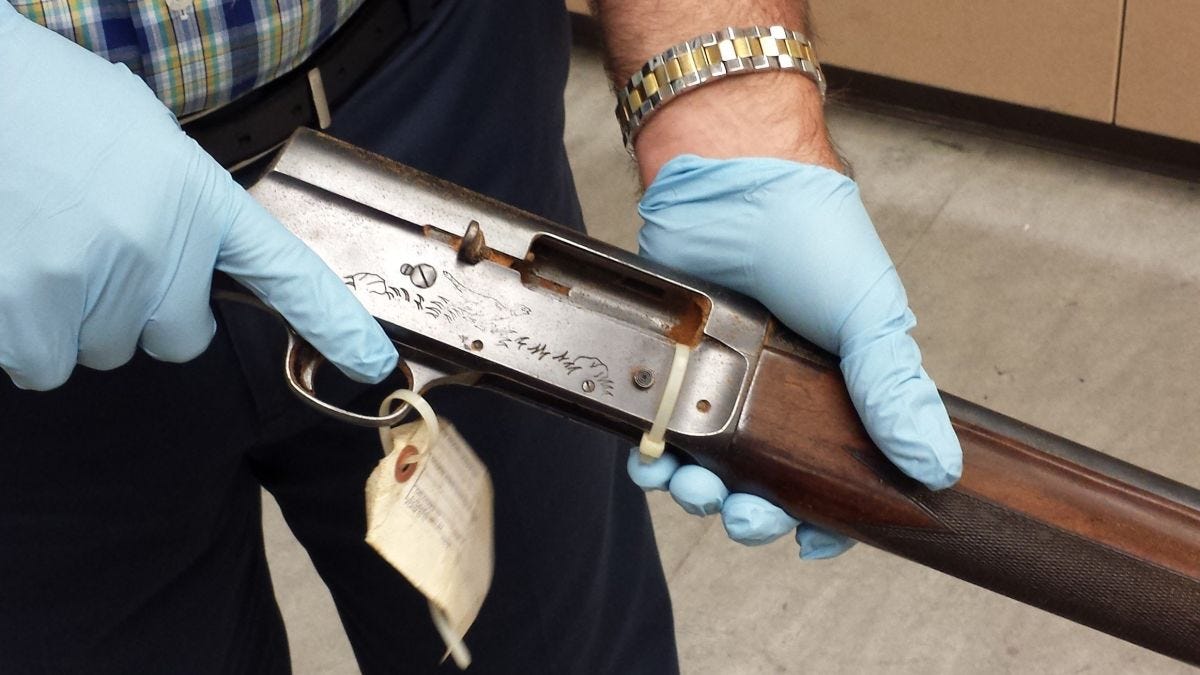

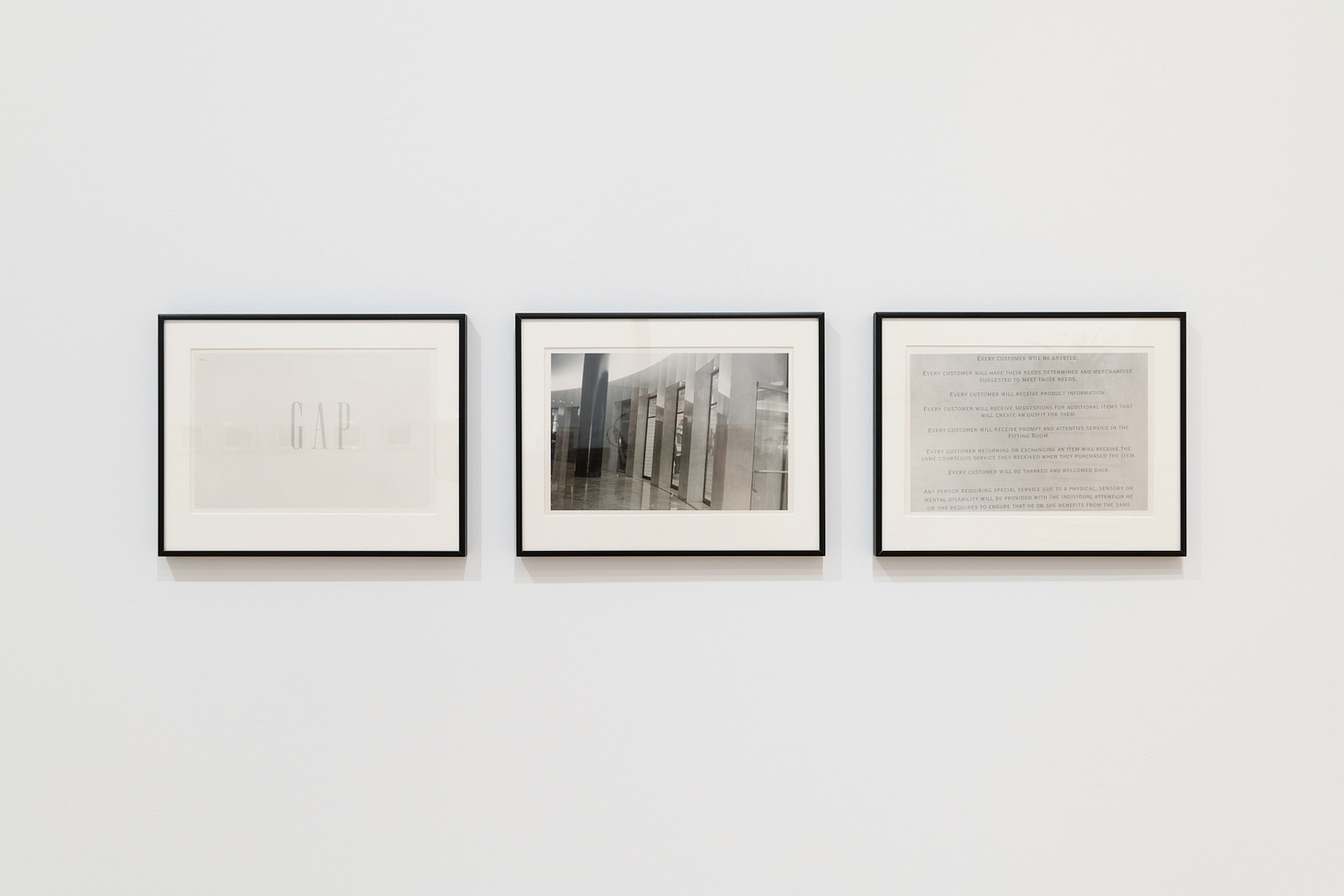

Also prior to the original exhibition, the group spent time exploring their subject in a different way. This “research” involved dumpster-diving materials discarded from Gap stores around New York City. Found Gap-branded shopping bags and shoe boxes appeared in the original show and are included in the current installation at Artists Space. Gap shoe boxes form a haphazard column underneath a step-cut dividing wall; Gap bags are stuffed into an odd retail environmental, which also features pages from employee training manuals, most pertaining to “loss prevention” strategies, which were also snagged on the dumpstering excursions. Portions of text boosted from the training manuals directing would-be Gap employees on how best to serve the customer and brand, wrap around the gallery walls, reading like an eerie, corporate Lawrence Weiner. Meanwhile, framed reproductions of the manuals’ text and black-and-white, vaguely clandestine photos of actual Gap retail stores, run along the walls. The pairing registers like a Hans Haacke site survey (he once taught AC2K members at Cooper Union) but with the unsettling, spectral presence of thoroughly diffused surveillance. If that’s not creepy enough, a convex store surveillance mirror appears among the installation’s assorted articles with the pilfered title Customer Service Is the Key to Loss Prevention (1993).

Commingle at Artists Space also includes a group of untitled-but-subtitled photographs from the original exhibition portraying AC2K members’ fresh-faced young selves sporting newly purchased Gap outfits in various emblematically charged New York City locations. Times Square—supremely iconic!; a Conran furniture store—not so iconic, but relatable; and at the office library of Art in America—a niche icon, of art-world sorts. Each photo shows the members not only dressed in The Gap’s then signature casual-cool outfits, but also captures them in postures of mocking self-awareness. Untitled (Times Square/Gap Grunge 2) (1992-93) finds the seven AC2K members exploring the intersection of counter-cultural cachet and its opposite, corporate homogenization at the intersection 7th Avenue and Broadway. The group parodies the supposed “individual” addressed by The Gap’s “Individuals of Style” advertisements by dressing in identical denim cutoff shorts and shirts, red bandanas, and circular sunglasses—items which were all purchased from The Gap. This sort of critical-yet-narcissistic mise en abyme would become AC2K’s go-to outfit for the remainder of the group’s lifespan.

Stop to ponder the tenability of self-reflective critique of a cultural era—one bifurcated equally between the art-world and consumer-world—while that era is still taking place. Consider the following trifecta of terms—space, time, and culture. They coordinate much of Fredric Jameson’s Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1991), a work of critical theory already firmly positioned by the early 1990s to encompass the cultural, and ultimately political, concerns of the decade. Jameson’s postmodernism is a contemporary capitalism without limit as it relates to these three terms. Space alone survives as a privileged remainder in Jameson’s schema after a maximal “explosion” or “prodigious expansion of culture throughout the social realm”3—one that cognitively subsumes history (opening a door for celebrant ideologues to announce a so-called end-of-ideologies, no less!). Does the seeming lack of any “Archimedean” vantage point for cultural critique then, by the 1990s, establish a deadlocked cultural politics of infinite frustration? Did the frenetic attack-and-parry style of “critique” AC2K adopted for seven years constitute an incessant attempt to outflank postmodernism à la Jameson with counter-cultural guerrilla tactics? Is it odd, then, that a group which took a capitalist culture without limit as their muse and punching-bag would, following their first exhibition, name themselves after their own pre-determined destruction-date—the turn of the millennium, the “2000” in “ART CLUB2000”?4

If AC2K took up consumption as implied by the commodity form as but one integral component of capital accumulation—one which acts to transform the individual at the level of personal consciousness and personal appearance—then with their fourth American Fine Arts, Co. show SoHo So Long (1996) the group turned to the obverse component of these material conditions: real estate speculation. This time, New York’s Soho neighborhood was enlisted as representative of the space in which “authenticity” squared off with advanced accumulation.

Perhaps the ur-site of modern gentrification, 1980s Soho became the first New York City neighborhood to reverse a decades-long cycle of decline by attracting investment capital. This capital arrived on the heels of high-end commercial galleries and their art collectors, who were in turn attracted by the neighborhood’s entrenched cultural cachet, having been a bohemian enclave synonymous with advanced art and DIY loft-living since the 1960s. By the mid-1990s the neighborhood’s ascent had become so intense that it even overwhelmed the galleries that had helped drive it. Many were forced to relocate to virgin territory, Chelsea. It was during this moment and amidst this milieu that AC2K selected its actors—not themselves this time, but a broader snapshot of personalities from the art world proper.

AC2K conducted a series of interviews with gallerists, art collectors, and critics about the Soho neighborhood and their own prospects for the future. These interviews helped to guide the construction of the 1996 Soho So Long installation which appeared at American Fine Arts, Co. and has, again, been re-presented at Artists Space. The installation oscillates between the interior and exterior of the gallery much like the original did. One of Artists Space’s galleries has been converted into a bland lounge, while the gallery windows have been soaped-up and obscured in a vaguely paranoid gesture, one cued with text to the coming arrival of a mock Old Navy store. A soda machine—a period antique, though not functional one—has been placed inside opposite a large light-box featuring a photograph of many of the New York art world’s then most influential gallerists, figures like Andrea Rosen and Pat Hearn. Inexpensive furniture separates the two large, luminous cuboids. A parody duplicate of Kenny Scharf’s “Scharf Shack” makes up third, adjacent, rectangular component. Scharf had installed the original “Scharf Shack” in the East Village’s Cooper Square and used it as a place to sell his own branded knickknacks. AC2K’s version is a one-to-one replica, derisive of Scharf’s original and his attempt at self-commodification.

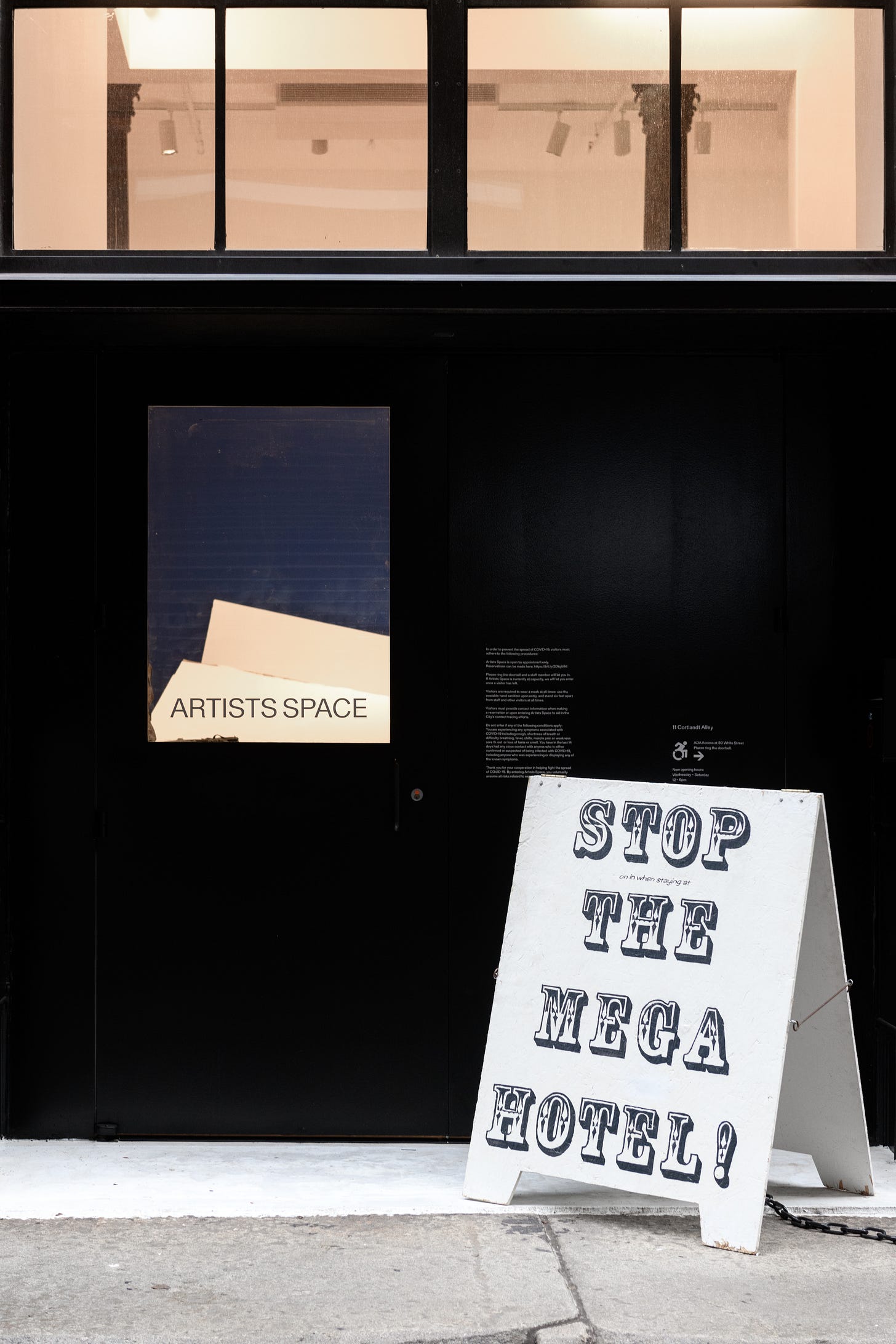

A humble sandwich board sign—which AC2K had placed outside of the original Soho So Long installation and which sits outside in the Artists Space reprisal—reads “STOP (on in while staying at) THE MEGA HOTEL!” referring to the then-looming opening of the Soho Grand. With its antique script and parenthetical text,5 it is a wimpy non-gesture, one that undercuts itself with equal parts resistance and preprogrammed resignation. It is also a clear, though overlooked, nod to the project’s art-historical lineage. The sign might as well read “STOP THE BOULEVARD HAUSSMANN BUILDING SOCIETY!” referring to the governmental development behemoth-cum-villain of Louis Aragon’s 1926 “novel” Le Paysan de Paris (Paris Peasant),6 which—along with André Breton’s Nadja (1928)—made up an early literary salvo in Surrealism’s attack on European culture following on the heels of Dada.

Readers follow Aragon through a wandering, first-person exploration of Paris’ Passage de l’Opéra, an enclosed nineteenth-century shopping center or arcade, which had, by 1926, fallen out of fashion and was slated for destruction and redevelopment by the BD Haussmann Building Society. Haussmann is portrayed, accurately, as a stereotypically corrupt and governmentally subsidized developer and the enemy of local shopkeepers inhabiting the Passage, who were being driven out by the redevelopment scheme and offered grossly inequitable compensation for their troubles.

Walter Benjamin saw the surrealist excursions into dilapidated Parisian surrounds recounted in Le Paysan and Nadja as potent form of escapism. The extended ledger of Benjamin’s considerations is worth reproducing here; for Benjamin, Breton’s Nadja, in particular, and the surrealists in general were:

The first to perceive the revolutionary energies that appear in the “outmoded,” in the first iron constructions, the first factory buildings, the earliest photos, the objects that have begun to be extinct, grand pianos, the dresses of five years ago, fashionable restaurants when the vogue has begun to ebb from them. The relation of these thing to revolution—no one can have a more exact concept of it than these authors. No one before these visionaries and augurs perceived how destitution—not only social but architectonic, the poverty of interiors, enslaved and enslaving objects—can be suddenly transformed into revolutionary nihilism. … They bring the immense forces of “atmosphere” concealed in these things to the point of explosion.7

If the “outmoded” implies a period of remove—a period of passed time in which something becomes obsolete, then Benjamin is not being very particular in defining this temporal allotment. There are many decades difference (a century or more) between his “first factory buildings” and “the dresses of five years ago.” “Benjamin does not distinguish among the truly archaic, the magically old, and the simply demodé,” as Hal Foster points out in his 1993 reading of this passage in his book, Compulsive Beauty.8 AC2K’s sphere of concern employs a similarly generous timespan regarding the condensation of mythologies9 that Soho had accumulated, for them, by 1996: where an avant-garde of yesteryear had transformed New York’s “first factory buildings,” iron constructions, into the city’s reigning artistic bohemia, one which was already far along in cashing in on its accumulated cultural standing.

Is anything simply demodé, or does the outmoded appearing in the guise of the out-of-fashion rather than the obsolete or out-of-use deserve more attention? AC2K’s inhabited concerns—youth-oriented consumerism, gentrification, reining art world legacies—seen en masse begin to converge around the operative principles of fashion as such. In Compulsive Beauty, Foster explores a surrealist mis-expression of the revelatory potential of Benjamin’s “outmoded” in the personage of Salvador Dalí, aka “Avida Dollars,” the derisive anagram Breton would use to brand Dalí as a sell-out. While Dalí did become the epitome of tacky artistic self-cooption in his later years, Foster’s argument centers on Dalí’s 1930s enthusiasm for art nouveau, which was by then quite demodé.

Benjamin singled-out art nouveau as expressing, in its approach to the problems of design and physical construction, a particular contradiction that had grown up with nineteenth century bourgeois culture: that its subjective life advanced with technological development. The style becomes more ornate apace with the expanding, dividing commercial conscience of this time—the birth of Benjamin’s “private person.” At about this time—this fin de siècle—or slightly before, according to Benjamin, “living space becomes … antithetical to the place of work.” Meanwhile, the actual building materials and techniques employed to create art nouveau constructions become less personal, less artisanal. Iron girder and concrete construction methods turn out serialized buildings. And yet art nouveau pushes back against this depersonalization imposed upon the built environment by technology and on the individual psyche by commerce: “in ornamentation,” Benjamin writes, “it strives to win back these forms for art.”10

An outmoded art nouveau in the 1930s should then be ripe with revolutionary “energies” ready to expose historical contradictions. According to Foster, Dalí plows past the latent tension between art and technology buried in art nouveau, in which Benjamin saw revolutionary or at least revelatory potential, opting instead to “celebrate” art nouveau as schlock simply for shock’s sake. Dalí’s target was austere modernism, the functionalist aesthetics that had supplanted art nouveau by 1930, ornament being, by then, the sworn enemy of modernism.11 In this sense, the outmoded becomes a reactionary turn of fashion, a tit-for-tat in cyclical commerce: “anachronism assists commodity innovation in the form of the demodé returned as à la mode, of the retro recovered a risqué.” And as Foster is quick to point out:

Today [1993] this dynamic informs cultural production both high and low … but it was first articulated by Dalí, who effectively displaced the surrealist practice of the outmoded with the surrealist taste for the demodé—with camp, if you like. … [R]ather than a cultural revolution keyed to disjunct modes of production, it abets compulsive repetition calibrated to smooth cycles of consumption.12

If the pop cultural zeitgeist of the 1990s had a psychic dimension, its most salient feature was most certainly sell-out anxiety. “The slacker,” one who simply eschewed these anxieties from the get-go, embodied, at the least, the most obvious and prevalent consummation of this 1990s cultural conundrum. However, in a 1994 opinion piece for the New York Times, Foster assessed a different “distinctive sensibility” of the moment, one in which the slacker is pushed to further extremes, to a “Cult of Despair” or fascination with “the abject,” the down-and-out, wretched individual. Foster’s argument was also (a)political: by the nineties, the subject of history shifted from “the Worker, the Woman, and the Person of Color” to “the Corpse”—touching upon an underlying social dynamic that is still very much with us today (although the 1990s-style desire to disembody has been supplanted in turn by a much differently fashioned one13). Foster offered the then recently deceased Kurt Cobain up as exemplar. After all, “what was the music of Nirvana about if not the Nirvana principle, a lullaby droned to the dreamy beat of the death drive?”14 But what drove Cobain to suicide? Not only abject resignation and depression, but a hopelessness spurred by the grunge rocker’s fraught relationship with his own success, caught as he was trying to reconcile a real sincerity in his musical ambitions with the inauthenticity of commerce. As the seven members of ART CLUB2000 saunter down 7th Avenue in Untitled (Times Square/Gap Grunge 2), are they not making the last self-authored statement possible—other than suicide15—concerning their own subjectivity before it is lost entirely, smoothed out of existence by the cycles of consumption?

In a recent Artforum review of the Artists Space exhibition, Domenick Ammirati sees AC2K’s work as institutional-cum-social critique in the lineage of the group’s predecessors-cum-pedagogues’ sited conceptualism—Haacke et al.—exploring “the possibilities and vacancies of the mediated and branded self”16 and training such critical tactics towards themselves. Ammirati alludes to “cognitive mapping,” the final frontier in the expanded field of institutional critique whereby the “site” of the institution in question is expanded to encompass a broad range of concerns if not global capitalism as such. This critical process would be expounded upon by Jameson in his Postmodernism and cited by Foster in his 1996 essay “The Artist as Ethnographer” to situate, or "site”, practices like the geopolitical excursions produced by artist Allan Sekula, particularly his photo study of the maritime mercantile Fish Story (1995).17 According to Ammirati, AC2K “maps” the narrower cultural geography of the aspiring young artist of the 1990s:

ART CLUB2000’s penetrations of the media may have more to tell us about local and aleatory networks. … This case study of the leveraging of cultural capital, from art school to gallery to art magazine to fashion magazine and beyond, gives the work an evidentiary quality, mapping a complex chain of interactions that evokes an (immaterial) cultural geography—a slacker Fish Story—and yet also intersects at every turn with the obdurate materialism of gentrification and precarious labor. Ultimately, AC2K aligned less with the contemporary dandy traipsing through niche media’s hall of mirrors and more with the return of the real, as Hal Foster theorized these things in 1996. Anthropologizing themselves, they were an unlikely example of the quasi-ethnographic position that their instructors had trailblazer and that so many artists continue to inhabit today.18

Ammirati is certainly spot-on in situating AC2K’s work as sited self-cognition but misguided in extending the scope of their “penetrations,” the raison d’être of their practice, to the material: late capitalist totality. As Jameson acknowledges, “cognitive mapping” was first established as a procedure by urban theorist Kevin A. Lynch in his 1960 study The Image of the City, where he found that the subjective sense of urban alienation registered by city dwellers tracked directly with how easy or difficult it was for them to mentally “map” their surrounds. Yet Jameson also acknowledges “the absence of any conception of political agency or historical process” in Lynch’s work, a limitation which he elsewhere ascribes to “the deliberate restriction of his topic to the problems of [the] city form as such.”19 A working concept of ideology borrowed from Louis Althusser and—to a lesser degree—Jacques Lacan, completes the projection.

The “cognitive map” obtains its critical force from connecting a chain of association that tethers the “local and aleatory” to the global, the immaterial to the most ultimately material—the “imaginary” vision of ourselves in our surrounds that Lynch registered with his municipal data to the “real” place we occupy in a global totality. Likewise, the “Slacker,” by definition, abstains from labor and thus capital, the two dialectical components that make the cognitive map spring to life. Parse AC2K’s oeuvre and ask: where’s the labor, where’s the capital? Granted, the group certainly explores art world labor and gentrification,20 but these concerns extend only as far as their own narcissism will allow. Where are the sweatshops in Singapore or Malaysia where The Gap clothing was being manufactured? Where are the strip mines in South Africa where ores were being extracted, capitalized—dematerialized and securitized—and reinvested in tony TriBeCa loft spaces? These dusty old Marxist concerns must have been too outré to be worth AC2K’s time.

Of course, just as Magritte never made pipes, the “cognitive map” is never the territory; any such account must rely on some additional step of aesthetic mediation to obtain its effects or risk losing itself in a mise en abyme of granular detail. In this regard, we are not too far afield from a return to the significance of Benjamin’s bourgeois “wish symbols.” While reflecting in retrospect upon his wanderings in the Passage de l’Opéra, Aragon is struck by a “detour,” a sudden reordering of his relationship to myth. Having “failed to recognize the gods in the street,” he admits: “I had not understood that myth is above all a reality…that it is the path of the conscious, its conveyor belt.” Aragon seeks out an explanation for the “great power that certain places, certain sights exercised over [him],” the intoxicating “mystery” contained in “everyday objects”:

The way I saw it, an object became transfigured: it took neither the allegorical aspect nor the character of the symbol, it did not so much manifest an idea as constitute that very idea. Thus it extended deeply into the world of mass…. It also seemed to me that time played a part in my bewitchment. While time lengthened in the same direction that advanced each day, each day enlarged the influence that these still desperate elements exercised over my imagination. I began to understand that their kingdom derived its nature from their newness, and that a mortal star shone over their kingdom. So they appeared to me in the guise of transitory tyrants, and in a sense the agencies of chance in relation to my sensibilities. Lucidity came to me when I at last succumbed to the vertigo of the modern.21

Such is one major aesthetic of Surrealism, the “mythology of the modern,” as Aragon finally calls it. For Benjamin, its power resides in its ability to unseat class power, to reposition this power’s claims towards transcendentalism as anything but. Such dialectic criticality has little effect if spelled out; it must be presented aesthetically, as an ecstatic experience of transcendentally equal or greater “mass.” At some point, every critical aesthetic of the modern, the lifeworld of the commodity, must register ecstatically as such an “ah-ha” moment—revelatory and not simply cartographic.22 We can certainly see why for surrealists such as Aragon, this experience was by all means akin to “intoxication.” But we find none of this ecstatic or revelatory “vertigo” in the installations of ART CLUB2000. Their precedent is not so much Surrealism then. They seem to furnish the “toxic”—the hopeless, terminal, and paranoid—in this “intoxication.” Wandering their mental landscape is akin to plunging deeper into vertigo tout court.

What if AC2K’s work harks back, past institutional critique, stopping before Surrealism, to hinge on the developments of an earlier predecessor: Minimalism and its Postminimalist successor, the epochal shift to the “theatricality” of “specific objects.” These predecessors asserted—in polemic contrast with critic Michael Fried—the philosophical position that an artwork does, in fact occupy the same space as its viewer.23 Artists, later labeled “conceptual,” soon concluded that this schema rendered the art object into an occasion or a paradoxical prompt with which they could appeal to the viewer’s mind—the perceptual framework we each carry around with us and experience the world through. Artists like Haacke then reinserted an overt politics into this paradigm, claiming that “a restricted conceptual art expands into the very ambition of cognitive mapping itself,” whereby “the paralogisms of the ‘work’ include the museum, by drawing its space back into the material pretext and making a mental circuit through the artistic infrastructure unavoidable.” And it is in this “expanded field”—Jameson’s “high and dry in space itself,” and its specifically postmodern “political content”—that AC2K’s work resides. “Utopian vision,” then becomes the moral criterion by which subsequent mixtures of spatialized art and politics must be judged.24

Things often went awry. The idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk had a negative resurgence at the time. Critics25 saw in it a means of reading the failed coordination medium-specific elements within the expanded field—“mixed media” if you like. The so-called October School of writers, pitched “medium specificity” against the Gesamtkunstwerk, elevating the former to a quasi-ethical imperative in art. Their undesired outcome was the success of a sort-of “anything-goes” pluralism—an art without criteria—which the Gesamtkunstwerk, recoded as “installation art,” is well positioned to accommodate.26 Here, Jameson sees Robert Gober’s installations as an ideal resolution; not as a space rife with artifacts teasing the mind-in-space but a space productive of a new concept of utopia. For him, it stands in contrast to Haacke’s “deconstruction”:

Haacke deconstructs: the fashionable word seems quite unavoidable in thinking of him (and recovers some of its original, strong, political, subversive meaning in his context). His art has a European culture-political corrosiveness; Gober’s is as American as the Shakers or Charles Ives, its absent community, its “invisible public” constituted out of readers of Emerson rather than of Adorno. I’m tempted to suggest that this form of conceptual art … differs from its opposite number in that it constructs, not an already existing concept of the type that Haacke and others take to pieces, but rather the idea of a concept that does not yet exist.27

As students steeped in the school of the “opposite number” and its tradition, AC2K looks less like the “class clown” or the “bookworm” that Ammirati makes them out to be. Theirs is Columbine aesthetics of destruction: they proved to be the smart but disgruntled—again, ultimately suicidal—nihilists in the back of the classroom, situated as they were at this fin de siècle and the dawn of “total reification.”

The group’s final exhibition of new work, Night of the Living Dead Author (1998), is a moribund and paranoid feat of juvenile regression, if not resignation. By this time, then mayor Rudolf Giuliani’s effort to clean up crime New York City was already a few years underway and apparently really harshing the general vibe. The show’s centerpiece, prominently displayed in Artists Space’s darkened basement: twin columns of cardboard cut-out “standees,” policemen or security guards with glowing red LED eyes à la Terminator and sashes reading “Punishing Enforcers of an Oppressive Regime.” A red LED scroll bar, Untitled (Statements Relating to the Death of the Author) (1998) names names of then-reigning art stars (the group included themselves in this accounting), implicating them all in their own respective self-commodification schemes against that infamous Barthesian decree. As if poised for their own art world slouch-towards-Bethlehem, the group included a Mies van der Rohe ottoman lent by Leo Castelli himself. With Untitled (Zombies) (1998) AC2K staged themselves in costume for the final time—deathly zombie attire complete with cheap-looking gore makeup.

With his Brillo Boxes, Warhol exposed the art object to the space of the commodity. With their nervous retail-inspired installation space, ART CLUB2000 drop the viewer into the fraught psychic space of the schizo subject of such reification. In an installation like Commingle the viewer wavers back and forth between customer, employee, and thief, addressed as all three at once. After all, this installation already seems to assume that virtually every viewer has either shopped at, worked at, or stolen from The Gap or some interchangeably similar retail venue, and addresses us accordingly.28

Again, we might return to Theodor Adorno, in retrospect, addressing Surrealism’s attachment to “the world of objects,” and its fixation on such things that register “obsoleteness” as an effect:

It seems paradoxical for something modern, already under the spell of the sameness of mass production, to have any history at all. This paradox estranges it … it becomes the expression of a subjectivity that has become estranged from itself as well as from the world. The tension in Surrealism that is discharged in shock is the tension between schizophrenia and reification…. In the face of total reification, which throws it back upon itself and its protest, a subject that has become absolute, that has full control of itself and is free of all consideration of the empirical world, reveals itself to be inanimate, something virtually dead. The dialectical images of Surrealism are images of a dialectic of subjective freedom in a situation of objective unfreedom. … [I]n them bourgeois society abandons its hopes for survival.29

Being both young and artists in cultures that prize such esoteric identity, not to mention youth.

See the exhibitions GAP: Individuals of Style, Museum of Contemporary Photography at Columbia College, Chicago, IL (April 9–June 4, 1994), https://www.mocp.org/exhibitions/1990/4/gap--individuals-of-style.php/ and Individuals: 20 Portraits from the Gap collection, National Portrait Gallery, London, (February 12–May 28, 2007), https://www.npg.org.uk/whatson/display/2007/individuals-20-portraits-from-the-gap-collection/.

Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1991), 48.

For more from Jameson on the thorough permeation of “culture” throughout the “social realm,” the necessity of “critical distance" in “cultural politics” and said distance’s disappearance in “global space" of postmodernism see Postmodernism, 48-49.

The parenthetical text appears in small print on the sign, totally illegible at a passerby’s normal viewing distance.

Louis Aragon, “The Passage de l’Opéra,” in Paris Peasant, trans. Simon Watson Taylor (Boston, MA: Exact Change, 1994). See especially 24-32.

Walter Benjamin, “Surrealism: The Last Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia,” in Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings, ed. Peter Demetz, trans. Edmund Jephcott (Boston, MA: Mariner Books, 2019), 192.

Hal Foster, Compulsive Beauty (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993), 158.

See Aragon on “a mythology of the modern” in Paris Peasant, xii, and note 21 below. Foster reads Aragon as a “modern mythology of the marvelous,”* the “outmoded” exploding and disrupting latent tensions hidden in the otherwise smooth synchronicity of bourgeois desires—both old and new—condensed in the lived experience of the modern. Foster, Compulsive Beauty, 173-74. *For more on “the marvelous” according to Foster, see Part 1 of this series.

Walter Benjamin, “Paris, the Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” in Reflections, 164.

Foster, Compulsive Beauty, 182-87.

Ibid., 187.

Reification tout court!

Hal Foster, “Cult of Despair,” New York Times, December 30, 1994, A31, http://nytimes.com/1994/12/30/opinion/cult-of-despair.html.

Though “suicide” was the group’s ultimate plan for itself—as a group—in a sense, from the start.

Domenick Ammirati, “ART CLUB2000,” Artforum 59, no. 4 (January-February 2021): 159-160.

Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, 51-54, 413-18, also 158, and Hal Foster, The Return of the Real (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996), 184-85, 189-90.

Ammirati, “ART CLUB2000,” 160.

Jameson, Postmodernism, 415, 51.

The group mounted a few shows abroad during their tenure, including Working! (1995) at Forde in Geneva, Switzerland where they created a faux office-space and displayed photographs of various gig sites the members of AC2K and their friends regularly occupied from 9 to 5. They also shot a video, Untitled (Cyclones at Travail) (1995), of the Forde staff feeding swans in a local park while listing all the various day jobs they had held down before working at the space. The photos and video are on display at Artists Space. These works speak to the narrow kind of woe-is-me, am-I-a-real-artist anxieties many an artsy, aspirational twenty-to-thirty-something in any major metropolis would have regarding moonlight employment.

Aragon, “A Feeling for Nature at the Buttes-Chaumont,” in Paris Peasant, 112-16.

Rachel Whiteread’s Turner Prize-winning temporary public sculpture House (1993), the cast concrete void of a demolished apartment building in London, melds a type of social cartography of redevelopment and gentrification with the revelatory surrealist relic, all by appealing to—that is, by being brutally forthright about its debts to—minimalist and postminimalist sculptural phenomenologies—namely Bruce Naumann's voids and Robert Smithson's site specificity.

The minimalists, along with their Pop art contemporaries, managed this phenomenological ground shift by welcoming the serialized objects that abound in modern industrialized societies as is into the artistic canon—that is, without also importing those societies’ contradictions à la art nouveau or adding additional layers of aesthetic mediation, as Surrealism did. See Hal Foster, “The Crux of Minimalism,” in Return of the Real, 34-70. Duchamp’s Readymade also deserves mention here.

Jameson, Postmodernism, 157-59.

Including Jameson: Ibid., 162.

See Walter Benjamin on Baudelaire and the flâneur in “Paris, the Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” in Reflections, 167-68. The constellation of concerns I have raised in this piece—the commodity, novelty, fashion, frivolity, mise en abyme, Gesamtkunstwerk, reification and death—certainly belong to a historical dynamic with roots running much deeper than the 1990s.

Jameson, Postmodernism, 162-63.

See Tao Lin, Shoplifting from American Apparel (Brooklyn, NY: Melville House, 2009).Lin’s autographical novella offers readers this subject with the same assumptions, though it is set in the following decade. Likewise, its titular subject was certainly The Gap's decennial successor.

Theodor W. Adorno, “Looking Back on Surrealism,” in Notes to Literature, ed. Rolf Tiedemann, trans. Shierry Weber Nicholson (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019), 104. Emphasis mine.